THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY: A JOURNEY COVERING OVER TWO CENTURIES

Is it possible to summarise the history of photography clearly and concisely?

Well, it may be challenging but it’s far from impossible.

The history of photography spans more than 250 years.

But for convenience, we’ll say that its beginnings lie in the first, primitive impressions of images on paper using sunlight, dating back to the first half of the 1700s. From that point onwards, a multitude of different experiments were conducted over the following years.

What makes history of photography so unusual is that it is intrinsically linked with humanity’s industrial development towards the contemporary world: a global and capitalist society driven by mass consumerism. So, the history of photography has gone hand in hand with technological progress, new economic models and the profound social changes that occurred between the end of the 1700s and the following century. These changes would significantly reduce the power of the aristocracy, see the bourgeoisie and working class climb the social ladder and lead to the emergence of modern industrialised nation states as we know them today.

Throughout this process, the history of photography has often crossed paths with the other visual arts, especially painting. Photography and painting have had somewhat of a love-hate relationship over the years, one that would eventually see photography accepted as an art form in its own right, and not a mere technological application for reproducing images. But this was only after years of fierce debate involving many famous artists (and some judges too!)

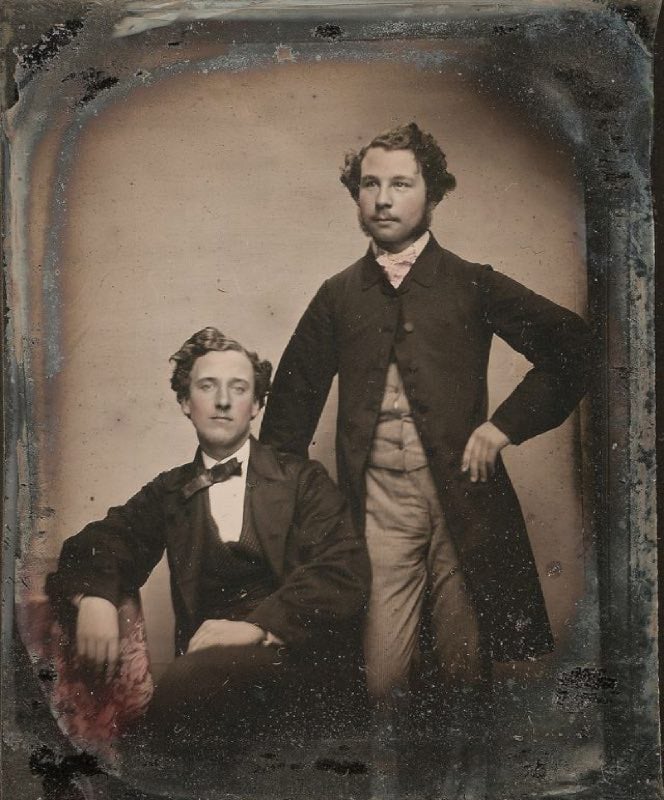

The innovation of photography created new customs among the emerging middle classes that differed from the ancient traditions of the aristocracy. For example, the paintings usually commissioned to portray the members of the richest families were progressively replaced with photographs, which were now accessible to less wealthy families too. As we will see, the history of photography is the story of not just technological innovations, but social ones too.

For ease of reading, we have broken down the history of photography into seven major stages:

1. THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY: WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

2. THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY: FROM FIRST STEPS TO DAGUERREOTYPE

3. JACQUES DAGUERRE AND DAGUERREOTYPE

4. FROM EARLY ADOPTERS TO THE FIRST PHOTOGRAPHIC BOOK

5. TECHNOLOGICAL EVOLUTION AND THE WIDESPREAD USE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

6. THE BIRTH OF THE MODERN PHOTOGRAPHIC INDUSTRY

7. PHOTOGRAPHY GETS REAL: HANDHELD CAMERAS AND COLOUR PICTURES

Let’s start our journey!

1. THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY: WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

It all began with the concept of “impression”: this procedure used a chemical reaction involving one or more substances exposed to sunlight to imprint an image onto a physical substrate. This, in a nutshell, is the process that led to the invention of photography.

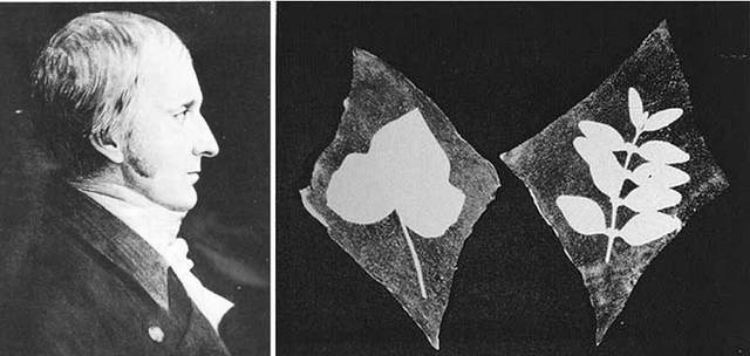

Following their discovery in the first half of the 1700s, thee began a long period of experiments into photosensitive materials – substances that react when exposed to light. The first attempts at impressions, like every new technology, were primitive and yielded imperfect results. Imagine a sheet of paper dipped in a jar full of photosensitive fluid, which is then removed, has objects place on top of it and exposed to sunlight. The area exposed to the light turns black while the areas covered by the objects remain light.

This early experiment was attributed to English potter Thomas Wedgwood (1771-1805). He filled ceramic pots with silver nitrate, then soaked paper or leather sheets in the chemical, placed objects on top of the sheets and exposed them to sunlight. Wedgwood discovered that the “images” imprinted via this chemical reaction deteriorated rapidly if exposed to sunlight, while if placed in the dark and illuminated with a candle or a lamp, they didn’t. This discovery is said to have been made in 1791.

This is an extremely simplified account of the first step in the history of photography. It all began with a chemical reaction that coloured a sheet of paper in the areas exposed to sunlight. When we step back and think that this was the beginning of a long road that took us to black and white photographs, then on to colour photos and, eventually, Polaroids, it’s astounding what humankind is capable of inventing when we refuse to give up at the first hurdle.

2. THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY: FROM FIRST STEPS TO DAGUERREOTYPE

The first experiments with photosensitive materials dating back to 1791 may have obtained modest results, but they undoubtedly stimulated mankind’s creativity. Looking back at the history of photography from where we stand today, it’s clear that those who attempted to realise the medium’s potential had intuited its infinite possibilities, and many were driven by the promise of monetising their results.

Two of the smartest characters in our story are the Frenchmen Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. They met in 1800 and began a collaboration that took Wedgewood’s intuition and pushed it further by inventing new techniques and using new materials. Niépce, intrigued by this primitive version of photography, looked for a way to obtain from the process a durable image that wouldn’t deteriorate with time.

His first invention was a complicated procedure that used a sheet of paper soaked in silver chloride and exposed in a little camera obscura. But this gave him the negative of an image with bright imprinted areas on a dark background. So he then turned to bitumen of Judea as a photosensitive material instead. He sprinkled the substance on a pewter plate, placed an engraving between the plate and a light source, then let light filter through the engraving and imprint the plate beneath. The light penetrated through the thinner parts of the engraving, hardening the bitumen. The plate was then washed with lavender oil, with the harder parts sticking to the plate, while the exposed parts were etched with aqua fortis and the final plate was used to print the image on a sheet of paper.Niépce called this laborious procedure, whichresembled traditional printing more than it did photography, “heliography”.

3.JACQUES DAGUERRE AND DAGUERREOTYPE

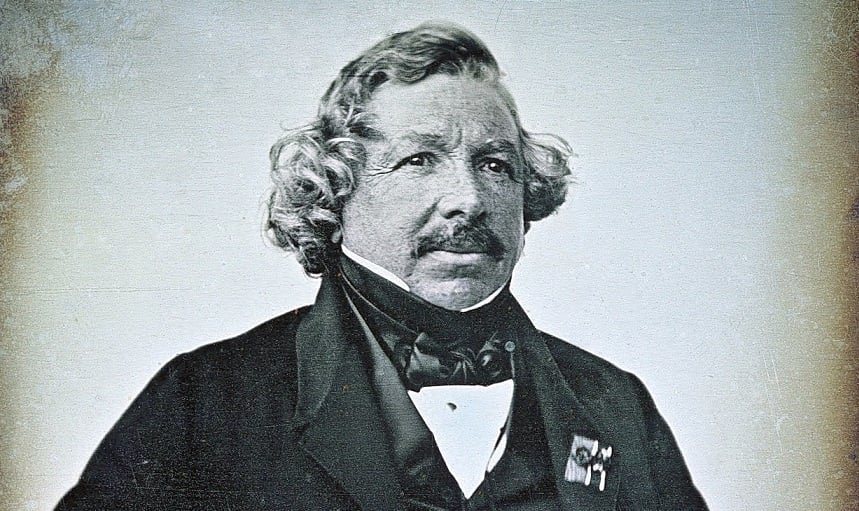

In 1827, on his way to visit his brother in London, Niépce met Daguerre in Paris. Daguerre had heard about Niépce’s experiments and was an innovator in his own right, although he came from the more traditional visual arts. As a matter of fact, Daguerre was quite a successful painter in Paris. He was famous for inventing the “diorama”, a special theatre for displaying paintings in which lighting tricks and other techniques were used to alter perspectives.

The two men went into business together, signing a ten-year contract to market their discoveries and work in synergy to refine the technology for impression on photosensitive materials. A few years after Niépce’s death, Daguerre showed the world his invention: the daguerreotype. This technology used a copper plate coated with a thin sheet of polished silver that, placed over iodine vapour, reacted to form silver iodide. Once exposed to light in a camera obscura, it turned back to silver in proportion to the quantity of light received. The resulting image was not visible until exposed to mercury vapour and then stabilised in a salt solution.

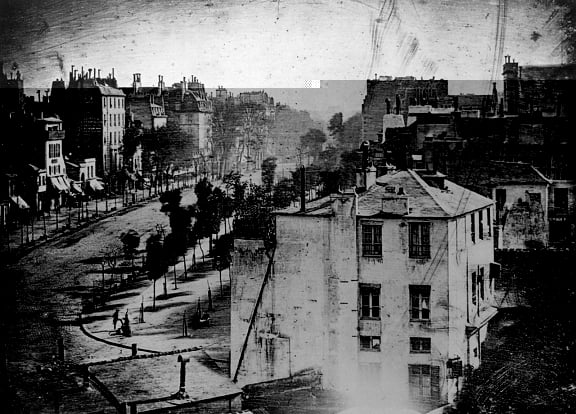

In 1839, Daguerre was looking for funding to monetise his discovery when he was contacted by François Aragoun, a French politician keen to purchase the patent for his chemical process. In the same year, the Gazette de France newspaper reported with great fanfare a new invention that made it possible to “paint with light”. The process was unveiled to the public for the first time on 19 August 1839. François Aragoun described this technique as “daguerreotype” and obtained an endorsement from the painter Paul Delaroche, who praised the high level of detail of this type of image and declared that artists and engravers shouldn’t feel threatened because they could use this new invention for preliminary studies of landscapes.

Later, Daguerre published a manual entitled “Historique et description des procédés du daguerréotype et du diorama” outlining the process for both Niépce’s heliography and daguerreotype. He also patented his invention in England, receiving royalties for its use. Daguerre also produced and sold his own version of the “camera obscura”. Madeof wood, it came withlenses offering a 40.6 cm focal length and f/16 aperture, and sold for 400 francs. From that moment on, his invention and techniques gradually spread around the world, spurring further experimentation and attempts to improve them.

4. FROM EARLY ADOPTERS TO THE FIRST PHOTOGRAPHIC BOOK

As the popularity of daguerreotype spread and the technology improved, more and more public demonstrations were performed to demonstrate the process that produced the very first “photographs”. Audiences were astonished by the results: harnessing the power of light to imprint such a detailed image onto a solid medium was simply amazing.

The process had one major drawback: initially, the exposure time needed to imprint the plate was at least 8 minutes. An awfully long time, tolerable for landscape but unbearable for a human being forced to remain still. The result was very static portraits in which the subject often appeared with their eyes closed. This problem was resolved by reducing exposure time to just 30 seconds through the introduction of cameras with an f/3.6 aperture and daguerreotype plates offering improved sensitivity thanks to the use of bromine and chlorine vapours. The silver substrate was also enhanced with gold chloride.

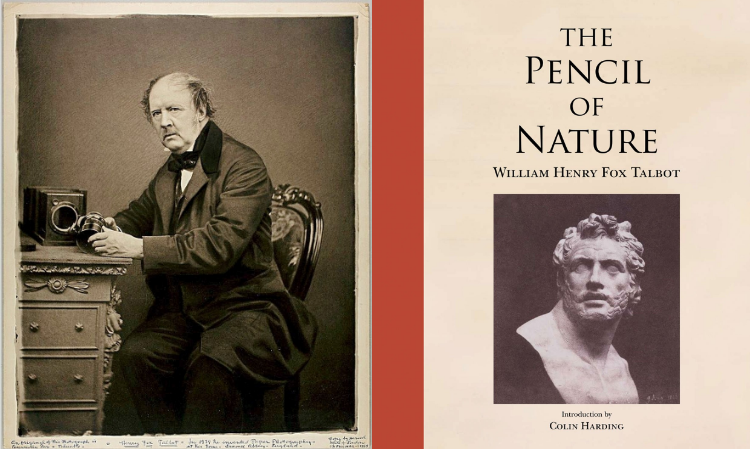

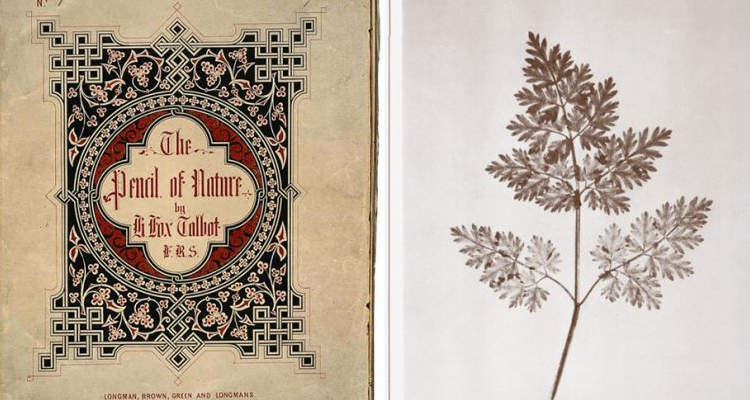

Daguerre’s technique continued to be improved upon until 1841, when calotype was introduced by William Fox Talbot. Calotype adopted the concept of developing a picture using a photo “negative”. With this approach, the exposure needed was just a few seconds because the picture was developed from the imprinted negative using an additional chemical process: the imprinted paper was dipped in a solution of silver nitrate and gallic acid, exposed to a source of light and then dipped in a second solution that helped to form the picture.

Following Daguerre’s example, Talbot patented his invention in England so he could make money out of it. From 1844 to 1846, he published “The Pencil of Nature”, one of the very first photographic books, containing 24 calotypes.

5. TECHNOLOGICAL EVOLUTION AND THE WIDESPREAD USE OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Thanks to continuous technological improvements made throughout the world, photography kept spreading and photographic labs sprouted like mushrooms everywhere. In New York City alone, there were more than 80 laboratories by 1850. And it was in America that silver plates began to be produced using steam-powered machines and then given an electrolytic treatment that resulted in a better product.

The rapid spread of photography meant it was soon accessible to every social class and no longer the preserve of the wealthy. The most commonly used methods were Daguerreotype and calotype. Daguerreotypewas considered of higher quality because it produced only one copy, leading it to be perceived as more valuable by customers, plus it didn’t have the print flaws typical of calotype.

Then along came a new technology that replaced every other technique in America thanks to its better quality: the collodion process. Glass or metal plates coated with collodion yielded excellent negatives for producing carbon or albumen prints.

Collodion plates had to be exposed while they were still wet and developed shortly afterwards, with prints delivered to the customer in a matter of minutes. In a further technological development, the use of underexposed collodion plates to obtain a negative by applying a dark surface to the reverse side gave birth to two more techniques: ambrotype, using a glass plate, and tintype, using a metal plate.

6. THE BIRTH OF THE MODERN PHOTOGRAPHIC INDUSTRY

The unstoppable growth of photography led to increasing demand for specific materials, instruments and components. Dedicated factories and laboratories soon sprung up. For example, at one point around 60,000 eggs were used every day in Dresden to produce albumen paper! Photographic laboratories were organised like assembly lines, with a specific task for every single worker.

Someone prepared the plates, which were brought to the photographer for exposure and then delivered to another colleague for development and, finally, fixation in a dedicated room. There were also people specially trained to coach customers on the best poses to take.

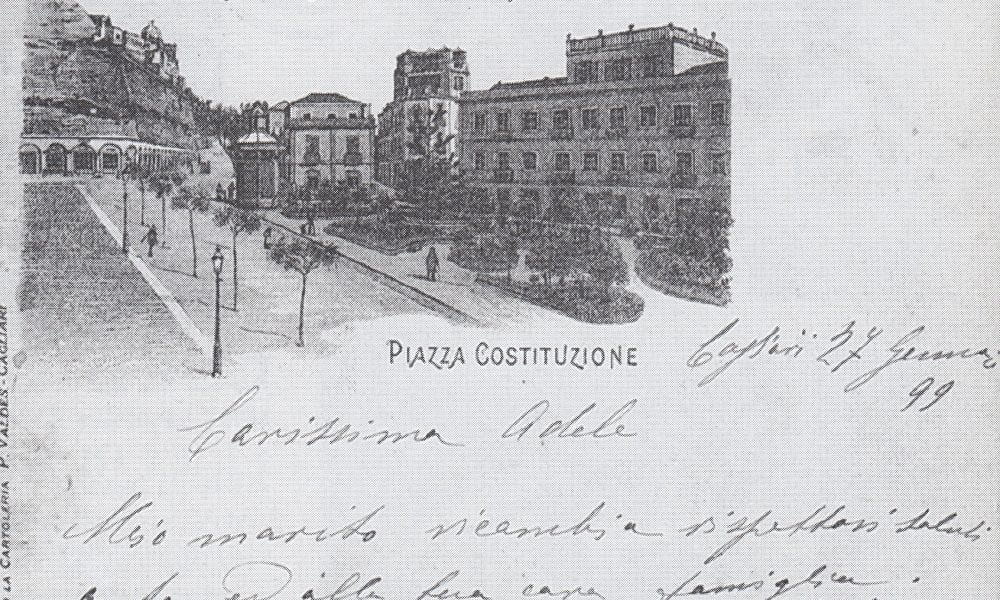

Family photo albums became very popular, as did landscape photography and postcards of celebrities, monuments, cityscapes, landscapes and picturesque views that were sold to tourists. It was the beginning of the mass production of prints and postcards.

Another significant driver towards mass production and the birth of giant photography companies was the thriving optical industry: the production of lenses and cameras was now big business and saw the growth of major companies like Kodak, Leica, Ilford and Voigtländer. And so, during the second half of the 1800s, mass production helped to democratise analogue photography.

7. PHOTOGRAPHY GETS REAL: HANDHELD CAMERAS AND COLOUR PICTURES

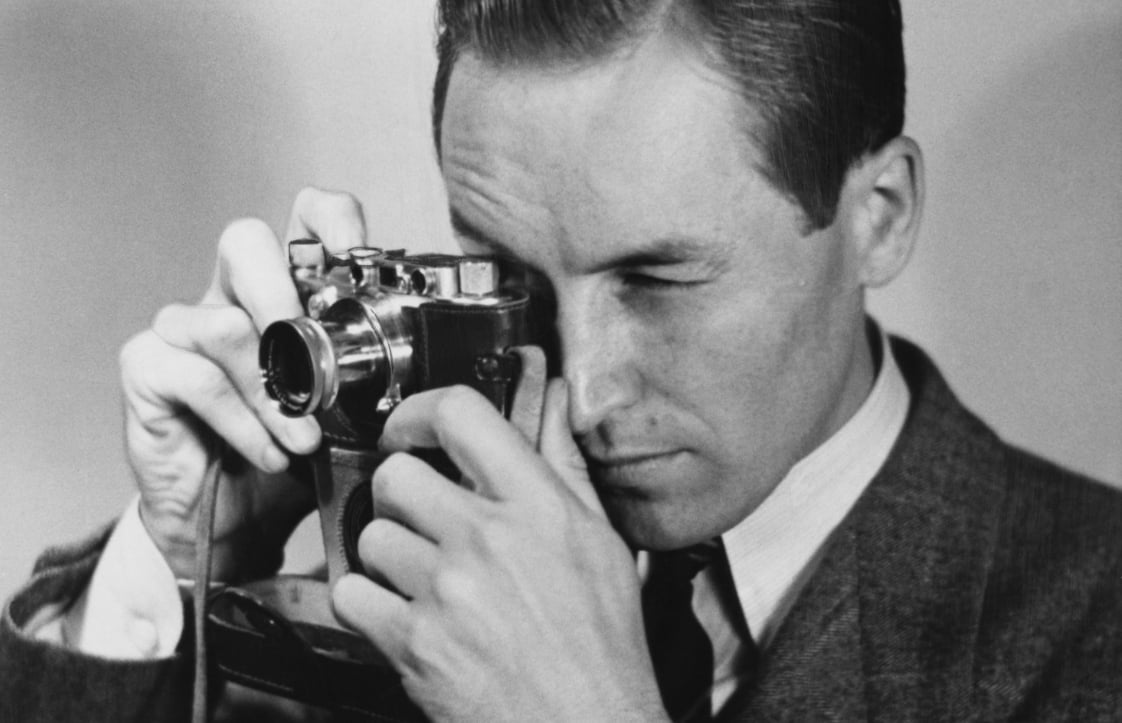

Photographs soon became seen as documentary evidence.

They became essential for journalists and adventurers who roamed the world taking pictures everywhere they went, now accepted as a legitimate way of reporting facts for newspapers around the world.

With such steady growth, the instruments used to take and develop pictures improved, becoming smaller and easier to use. This helped journalists and reporters to capture the biggest events on the spot, right there and then.

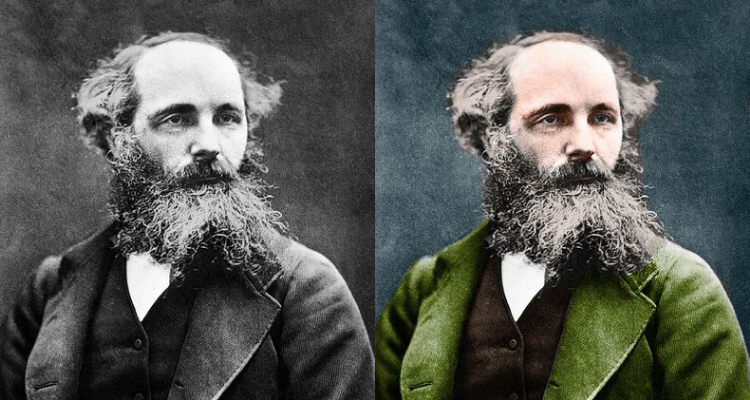

There was just one essential detail missing to make photography the perfect medium to capture reality in all its detail: colour. Pictures where still black and white. To make them look more realistic, photographers tried to colour them in using aniline-based pigments in some areas of the picture. But developing the technology for taking true colour photos proved to be a hard nut to crack. It began in 1859, with the experiments of James Clerk Maxwell, who discovered that it’s possible to obtain colour pictures with a process called additive colour. Maxwell overlapped three images taken in the primary colours of red, green and blue to create one single colour image.

This intuition was further refined and led to the discovery of subtractive colour mixing, which eventually saw the launch of Kodachrome photographic film in 1935. It used subtractive colour mixing to incorporate into the film three different photosensitive layers corresponding to the frequencies of red, blue and green. Kodacolor film came shortly afterwards, in 1941, making the home development of colour negatives possible for the first time.

PAINTING VERSUS PHOTOGRAPHY

The relationship between photography and painting is worthy of separate discussion.

It’s a relationship that has always been special, with inevitable divergences and differences leading photographers and painters to continuously swing between getting closer to and moving away from each other. As a result, the path towards photography’s recognition as a legitimate art form long and arduous.

The postcards and small photo prints initially sold to the public weren’t always of good quality. It all depended on how carefully the pictures were taken, what materials were used and many other variables.

For a traditional visual artist with a keen sensitivity for aesthetics, photographs could look cold and impersonal compared to the hand-painted portraits that were the accepted standard in centuries past. This led painters who were intrigued by photography to approach the medium more creatively. They prepared elaborate backdrops, and suggested bold poses or flamboyant clothes and accessories to achieve a more expressive effect in pictures.

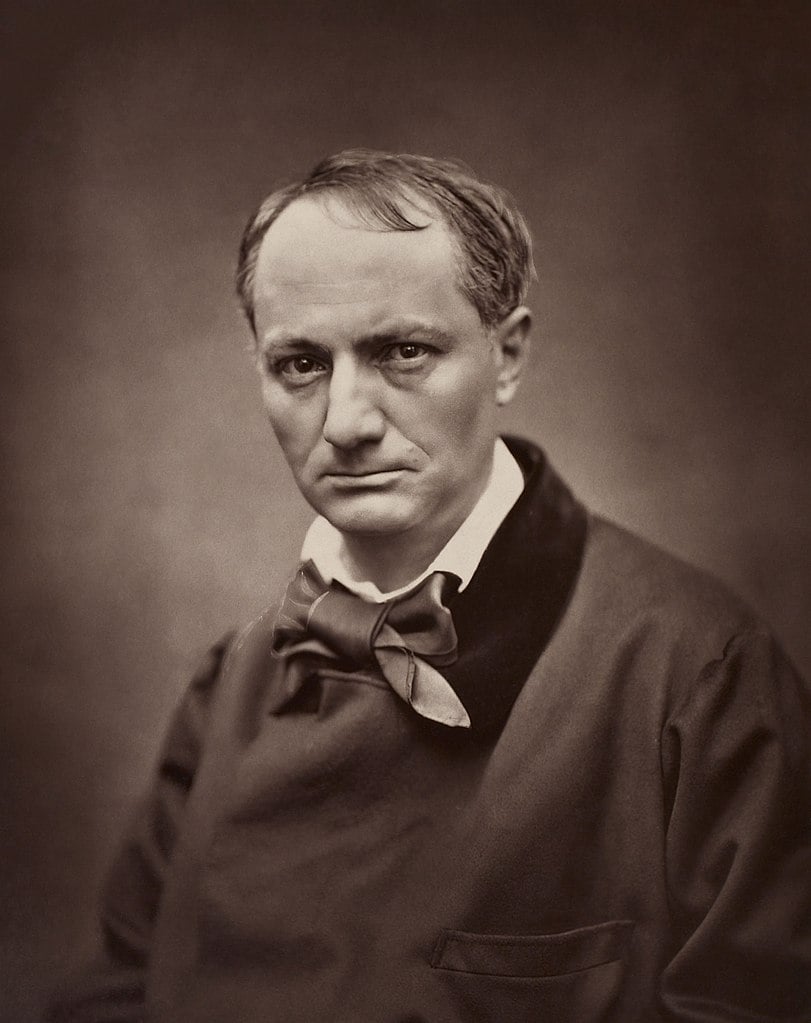

Whether these photographers came from painting, sculpture or theatre, all learned to play with different framing and lighting to improve the aesthetics of the picture. One such artist trying to take photographs using the techniques of the more celebrated traditional arts was Nadar. An imaginative artist from Paris with a strong character, Nadar was famous for taking the first aerial photograph in history while flying in a balloon equipped with a camera in 1858. Another notable contemporary was Etienne Carjat.

Celebrities like Charles Baudelaire, Gustave Courbet and Victor Hugo were photographed by these two artists.

FINE-ART PHOTOGRAPHY: EDITING AND AN ARTISTIC APPROACH TO PHOTOGRAPHS

As soon as artists tried their hand at photography, they began experimenting to bring pictures close to paintings,with some unusual graphic effects. Indeed, rather than paintings starting to resemble photographs, pretty much the opposite happened. Photography lacked all of the means of expression given by shade, brush stroke and colour selection. For this reason, techniques like double exposure and photomontage were introduced. Dozens of different negatives would be used for a single picture, or two negatives with two different exposure times were combined into a single photo to create special effects, like showing the sky and the ground in the same picture.

While photography tried to imitate painting with some fancy techniques, painting took advantage of some features of photography, like precise detail. For example, the painter Eugenie Delacroix referred to photos of his subjects to capture the gestures of the celebrities he painted down to the finest detail.

Pictorial photography began to be considered a legitimate form of art after the first half of the 1800s thanks to end results that looked like real paintings. But this trend abruptly stopped at the beginning of the 1900s. Pictorial photography began to be abandoned and photography deliberately distanced itself from painting, establishing itself as a legitimate art form with its own defining features.

This new approach saw photography as a pure form of expression in its own right with no need for retouching afterwards. At the beginning of the 1900s in America, the straight photography movement encouraged people to hit the streets and capture the reality of life in the city by photographing ordinary people, construction sites, buildings, working-class neighbourhoods and cityscapes. It had much in common with the abstract aesthetics of cubism and associated artistic movements.

In seeking an independent and abstract identity, many different photographic techniques were reinterpreted and reinvented, producing pictures with a life of their own and visual effects that were light years away from a brush stroke. This gave us techniques like photomontage and collage, used by Dadaist artists. The epitome of this trend can be found in the work of artists like Man Ray, El Lisstky, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Paul Citroen.

THE DEFINITIVE RECOGNITION OF PHOTOGRAPHY AS A LEGITIMATE ART FORM

For reach the moment photography was accepted as a legitimate art form, independent from painting and considered of the equal importance and dignity, we have to travel back in time to a famous legal dispute in a French court: the Mayer and Pierson trial. It marked a curious yet key moment in the history of photography.

Photographers Mayer and Pierson took two other photographers to court in 1861 accusing them of reproducing without permission some of their pictures of the Count of Cavour and Lord Palmerston. Even back then, photographers could make a lot of money selling pictures of celebrities, making this a particularly bitter battle and one of the first to be fought over copyright protection.

The crux of the matter rested on whether photography was a legitimate art from. In court, Mayer and Pierson invoked the copyright laws of 1793 and 1810, but these only applied to traditional forms of arts recognised as such. Unfortunately, photography was not – or at least not yet – one of these.

To successfully assert their copyright, the two photographers had to demonstrate that photography should be considered a legitimate art form. The trial ended in 1862 with a verdict that recognised photography as an art form like any other, hence deserving to be legally protected by copyright law.

Despite the verdict, intellectuals remained reluctant to consider photography as a legitimate art form, and full recognition as such would not come until the twentieth century was well underway, finally taking their rightful place alongside paintings in art museums around the world.